So much of the Bible is based on God's faithfulness to the people of Israel.

Devarim

For the week of August 2, 2014 / 6 Av 5774

Torah: Devarim/Deuteronomy 1:1-3:22

Haftarah: Isaiah 1:1-27

The Bible: Israel's Title Deed

See, I have set the land before you. Go in and take possession of the land that the Lord swore to your fathers, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, to give to them and to their offspring after them. (Devarim/Deuteronomy 1:8)

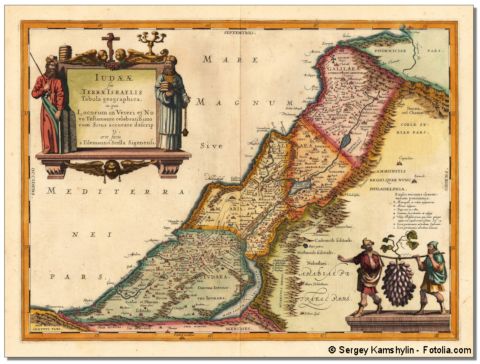

When reading the Bible, it doesn't take too long to discover that its predominant context is the people of Israel in the Land of Israel. That context doesn't simply function as a backdrop for the Bible's overall story; it's a crucial aspect of it. God's endeavor to eradicate evil and its effects upon his creation is based on the outworking of a plan. This plan begins with his calling Abraham to leave his homeland and settle in what was then known as the Land of Canaan (see Genesis 12:1-3). Almost as soon as he arrived, God said to him, "To your offspring I will give this land" (Bereshit/Genesis 12:7). Not only is this promise unconditional, it is also eternal. As God soon after added, "For all the land that you see I will give to you and to your offspring forever" (Bereshit/Genesis 13:15; see also 17:8). Even though Abraham had many sons besides Isaac (see Bereshit/Genesis 16 & 25:1-6), the promise was passed on to Isaac alone (Bereshit/Genesis 26:3-4). Of Isaac's two sons, only to Jacob, whose name was changed to Israel (see Bereshit/Genesis 32:28), was the promise of the land given (see Bereshit/Genesis 35:12).

Later on, under the covenant God gave to Israel through Moses at Mt. Sinai, Israel's remaining in the Land was contingent upon their faithfulness to that covenant. Eventually, due to their relentless pursuit of other gods, God sent prophets to warn them that, unless they changed their ways, foreign domination and exile would result. Through the Assyrians and Babylonians, that's exactly what happened.

But while retention of the Land was an expressed condition of the Sinai covenant, Israel's claim to the Land was based, as I have already explained, on God's unconditional, eternal promise to their forefathers. The tension between Israel's lack of worthiness and God's unconditional faithfulness through his promise is resolved through the New Covenant (see Jeremiah 31:31-33) as instituted by the Messiah (see Luke 22:20).

Much Christian understanding of the New Covenant assumes that the issue of Israel's claim to the Land becomes irrelevant. It is thought that the multi-national scope of the community of faith precludes Israel's nationalistic aspirations. It is inferred that the inclusion of non-Jews as part of the family of God to mean the superiority of a homogenized, generic, spiritual community. Yet knowing that some continuity with God's ancient plan as outlined in the Hebrew Scriptures must be retained, this quasi-national organization brands itself as "new" or "true" Israel. Detaching what is supposedly higher spiritual values from the lower natural ones, concern over the literal Promised Land, especially with its ancient attachments to the natural descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, is viewed as an archaic throwback to a below-standard epoch.

There are many problems with this approach to Israel and the Land, most importantly that nothing of this sort can be found in the Bible, the New Testament included. If such a redefinition was crucial to the understanding of God's explicit commitment to Israel through the forefathers, why is it not clearly expounded upon anywhere in Scripture? The Hebrew prophets fully expected that the natural descendants of the people whom they addressed (unfaithful Israel) would one day be fully restored to the Land and to God. Take what God says through Amos for example: "I will plant them on their land, and they shall never again be uprooted out of the land that I have given them" (Amos 9:15; see also Isaiah 54:7; Jeremiah 30:3; Ezekiel 37:21). Nothing about the coming of the Messiah or the writings of his followers detracts from this expectation. To spiritualize the prophetic literature by twisting its explicit intent undermines the Bible, since so much of its overall message is based on God's faithfulness to the people of Israel.

Affirming God's unconditional promise regarding the Land of Israel cannot be used by itself to justify the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948 or Israeli government policy since then. The political issues surrounding the establishment of the modern state need to be informed by great wisdom along with a desire for compassionate justice. However, it is essential to remember that a truly biblically based solution to the complex issues regarding the Middle East must include an acknowledgement of the Jewish people's God-given right to the Land of Israel.

---

Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Comments? E-mail: comments@torahbytes.org

Subscribe?

To have TorahBytes e-mailed to

you weekly, enter your e-mail address and press Subscribe

[ More TorahBytes ] [ TorahBytes Home ]