God imparts life to his people in spite of ourselves.

Naso

For the week of May 30, 2015 / 12 Sivan 5775

Torah: Bereshit/Numbers 4:21 - 7:89

Haftarah: Shoftim/Judges 13:2-25

Undeserved Blessing

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying, "Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying, Thus you shall bless the people of Israel: you shall say to them, The LORD bless you and keep you; the LORD make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you; the LORD lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace. So shall they put my name upon the people of Israel, and I will bless them." (Bereshit/Numbers 6:22-27)

God through Moses instructed the cohanim (English: priests) to bless the people of Israel with these words. The Torah concept of blessing has to do with imparting life, which of course comes only from God. When a blessing is pronounced upon another, it functions similar to a prayer, whereby the person is saying they would to God that he imparts said blessing on the one to whom the blessing is conferred. There is nothing magical about saying a blessing as if the speaker controls the elements of the universe and may do with them as they please. Rather, the speaker through words of blessing connects the recipient with already existing truths and the reality of God. The recipient is to be encouraged by such words and can expect God to respond in kind, that is if the context of the blessing is authentic. By that I mean that God cannot be tricked into blessing what he wouldn't bless.

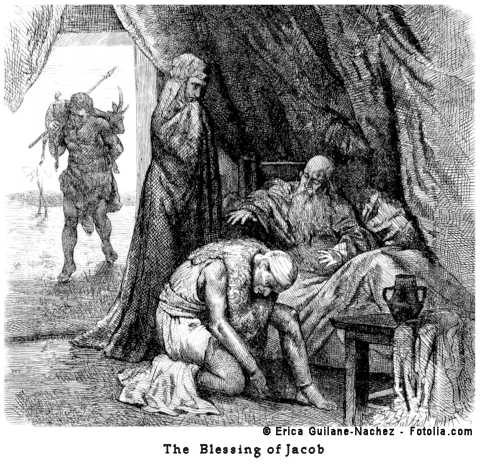

Before I continue, I should address the story of Isaac's blessing of Jacob that some may think contradicts this (see Bereshit/Genesis 27). Yes, Jacob certainly did deceive his father at his mother's urging and stole the blessing intended for his twin brother, Esau. But this is a case whereby God was using the dysfunctionality of that family to suit his own purposes. While Jacob was not the intended object of Isaac's blessing, God had determined that Jacob, not Esau, was to inherit the promises first given to their grandfather, Abraham. So in spite of all the intentions of the personalities involved, God had his way, and the blessing was appropriately bestowed upon the right party.

Now back to this particular blessing. In this brief space I want to look at one of its phrases, namely the words, "and be gracious to you." The biblical concept of grace among Bible believers is often used, but I am not sure how well understood. You may not be aware that the English word "grace" is used in the Bible to represent two different concepts depending on whether it is found in the Hebrew Scriptures or the New Covenant Writings. Normally, we would expect the translators to use different English words, especially since these concepts are so crucial to understand God and his relationship to people. The word translated "gracious" in the blessing we are looking at is a derivative of the Hebrew word "chanan," (the "ch" is pronounced as in "Bach"), which has the idea of showing mercy. That's why the early Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, called the Septuagint, upon which the New Covenant Writings strongly depend, uses the Greek word for mercy, "eleos.". Yet the word translated into English as "grace" in the New Covenant writings is "charis" (again, the "ch" is pronounced as in "Bach"), which is closer to the Hebrew concept of "chesed" (you should know how to pronounce the "ch" by now). Chesed includes chanan, mercy, but it's a lot more than that. Chesed is an overarching grand theme in the Hebrew Scriptures that refers to God's covenant love and faithfulness. It's the basis upon which his presence and power are bestowed upon his people. There is no chanan, mercy, without chesed, grace.

Why then do English translators use gracious in this phrase instead of mercy as the Septuagint does? It could be because the word "mercy" in English lacks the relational element found in this blessing. That God might restrain judgement, which is what mercy is all about, is not based on whim, convenience, or pragmatics, but rather arises from of a deep-seated commitment of love towards his people. Through these words of blessing the cohanim were connecting Israel with a deep sense of divine love they didn't deserve.

Perhaps Jacob's story, then, is a far more appropriate example of how God's blessing comes to us than at first glance. For just as Jacob was completely unworthy of the blessing he received, so are we. Even though we go about trying to get God's blessing in all sorts of inappropriate ways due to our dysfunction (what the Bible calls "sin"), we are blessed anyway. God blesses us not because of anything we have done, but rather because of his great mercy available to us through Yeshua the Messiah.

---

Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible,

English Standard Version®, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a

publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All

rights reserved.

Comments? E-mail: comments@torahbytes.org

Subscribe?

To have TorahBytes e-mailed to

you weekly, enter your e-mail address and press Subscribe

[ More TorahBytes ] [ TorahBytes Home ]