For the week of February 28, 2026 / 11 Adar 5786

Tezavveh & Zakhor

Torah: Shemot/Exodus 27:20 – 30:10; D’varim/Deuteronomy 25:17-19

Haftarah: 1 Samuel 15:2-34

Originally posted the week of March 7, 2020 / 11 Adar 5780 (revised)

As a jeweler engraves signets, so shall you engrave the two stones with the names of the sons of Israel. You shall enclose them in settings of gold filigree. And you shall set the two stones on the shoulder pieces of the ephod, as stones of remembrance for the sons of Israel. And Aaron shall bear their names before the Lord on his two shoulders for remembrance. (Sh’mot/Exodus 28:11-12)

This week, we look at one particular aspect of the elaborate garb of the Cohen HaGadol (English: Chief or High Priest). Over his main clothing, he was to wear an ephod, an apron-like overgarment with special spiritual significance. On each of the ephod’s shoulder pieces was a stone with the names of the twelve tribes of Israel. We read: “Aaron” (meaning he and his successors) “shall bear their names before the Lord on his two shoulders for remembrance” (Sh’mot/Exodus 28:12). The Cohen Hagadol, therefore, literally carried the names of the tribes into the presence of God.

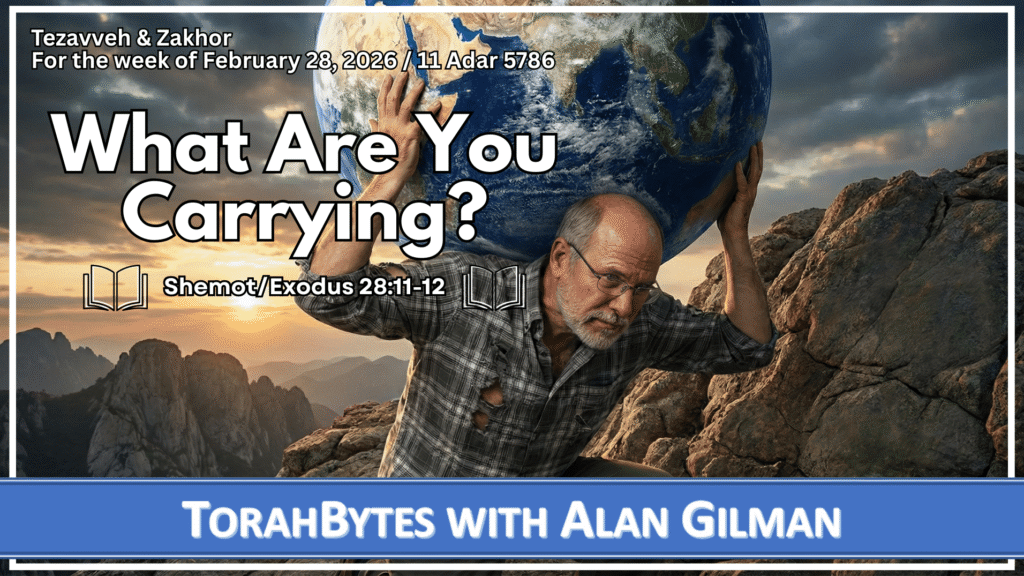

It isn’t clear whether the “remembrance for the sons of Israel” refers to the need for the Cohen HaGadol to remember the people of Israel in his priestly service, or if, in his priestly service, he was bringing the people of Israel to the remembrance of God. Either way, he was symbolically carrying the weight of the nation on his shoulders. That this was symbolic makes what he was doing no less real. He obviously wasn’t carrying the people themselves on his shoulders, but the burden of the cares of the nation is a heavy burden—one that would intensely affect most people.

Like the Cohen HaGadol, we carry burdens on our shoulders. Any responsibility, be it family, job, community, and so on, is a burden—a burden that may or may not feel burdensome, but a burden nonetheless.

God had clearly placed the people of Israel on the Cohen HaGadol’s shoulders. What you and I are to carry, however, may not be so clear. At times, we find ourselves overwhelmed by the cares and concerns of others. I suggest we take the time to ask God, whether or not these are our assigned burdens or if we have mistakenly put them on ourselves.

Sometimes we carry burdens God has given us, but we make them heavier than they really are. We might misunderstand the nature of the responsibility, leading us to take misguided courses of action. It is important to let God clarify for us how he wants us to do the things he gives us to do. Don’t be deceived into thinking that going extreme on something is the same as being faithful to God. Doing more than we should can be as destructive as neglect.

Frankly, I don’t know how common this is, but you might find this helpful. At times, I have felt burdened without knowing what I am burdened with. I find myself feeling heavy, thinking that I am personally struggling emotionally, when actually God is placing a concern on my heart for someone else. When you find yourself carrying a weight, but don’t know what it is, as in everything else, ask God what is going on. You might be bearing the burden of another. If so, then ask him what he wants you to do about it.

While very few are called, like the Cohen HaGadol, to carry the burden of an entire nation, what has God placed on your shoulders? Unlike those who find themselves overly burdened or misunderstanding what it is they are carrying, perhaps you have been too busy to notice. Few carry the responsibility level of a Cohen HaGadol, but all people carry something. As bearers of God’s image, created by him to fulfill his plans and purposes on earth, we all have some part to play, some burden to carry, a responsibility to fulfill.

Yeshua said, “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30). Often, when this is referenced, the lightness of his burden is emphasized so much that we forget there is still a burden to carry. What God calls us to do is not designed to crush us, but we are called to carry it.

Scriptures taken from the English Standard Version