For the week of June 4, 2016 / 27 Iyar 5776

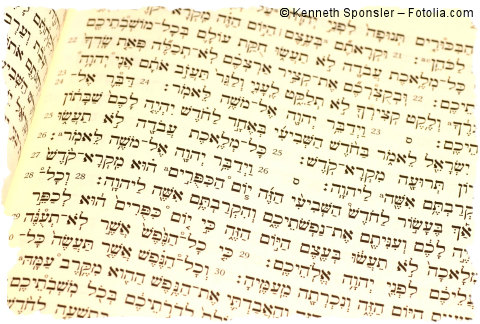

Be-Hukkotai

Torah: Vayikra/Leviticus 26:3 – 27:34

Haftarah: Jeremiah 16:19 – 17:14

Download Audio [Right click link to download]

But if they confess their iniquity and the iniquity of their fathers in their treachery that they committed against me, and also in walking contrary to me, so that I walked contrary to them and brought them into the land of their enemies—if then their uncircumcised heart is humbled and they make amends for their iniquity, then I will remember my covenant with Jacob, and I will remember my covenant with Isaac and my covenant with Abraham, and I will remember the land. (Vayikra/Leviticus 26:40-42)

Here in the last weekly portion of the third book of Moses, we read of the conditions under which God would restore the people of Israel to a right relationship with himself and return them to their land. The covenantal reference in the quoted verses above is key in understanding God’s unique arrangement with Israel.

This week’s portion describes the blessings of obedience and the consequences of disobedience under the covenant arrangement established through Moses by God at Mt. Sinai. As long as Israel would adhere to God’s commands, they as a nation would thrive. But should they reject God’s ways, breaking this covenant, they would experience terrible circumstances, culminating in oppression by their enemies and removal from their land.

Should this occur, which indeed it did, God made provision within the Sinai covenant for restoration to himself and to the land. But note that this provision is not based on the Sinai covenant, but on the earlier one made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Israel’s existence as a people, its habitation, and its role among the nations of the world were established, not by Sinai through Moses, but through God’s unconditional promise to Abraham (see Bereshit/Genesis 12:1-3) and passed down to Isaac and Jacob. The Sinai covenant with its conditions of blessings came about as a result of God’s deliverance of Israel from their oppression in Egypt, a deliverance also rooted in his earlier covenant with the patriarchs. This is what we read in Shemot (the Book of Exodus):

During those many days the king of Egypt died, and the people of Israel groaned because of their slavery and cried out for help. Their cry for rescue from slavery came up to God. And God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. (Shemot/Exodus 2:23-24)

The earlier covenant is the driving force behind all God’s dealings with Israel. So that even if Sinai resulted in failure, which it did, the covenantal foundation would survive. That’s why God’s judgement upon Israel could never be his final word to them. Even after rejecting God by turning to other gods and suffering the threatened consequences, there would always remain a right of appeal to unconditional promises that predate Moses.

This is also why a new covenant would one day be necessary. Jeremiah in chapter 31 of his book looked beyond the day when these words of judgement would be fulfilled to a new covenantal arrangement that would finally resolve the sin problem that continually beset Israel under the Sinai arrangement (see Jeremiah 31:31-33). That God’s affirmation of his ongoing faithfulness to Israel is based on their being the offspring of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is stated a couple of chapters later (Jeremiah 33:23-26).

The establishment of the New Covenant on the foundation of the patriarchs provides hope for Israel’s full eventual restoration (see Romans 11:28). More than that! Knowing that the New Covenant is rooted in unconditional promises assures all its participants, whether Jew or Gentile, of God’s ongoing faithfulness to them.

All scriptures, English Standard Version (ESV) of the Bible