For the week of October 4, 2025 / 12 Tishri 5786

Ha’azinu

Torah: D’varim/Deuteronomy 32:1-52

Haftarah: 2 Samuel 22:1-51

Originally posted the week of September 18, 2021 / 12 Tishri 5782 (updated)

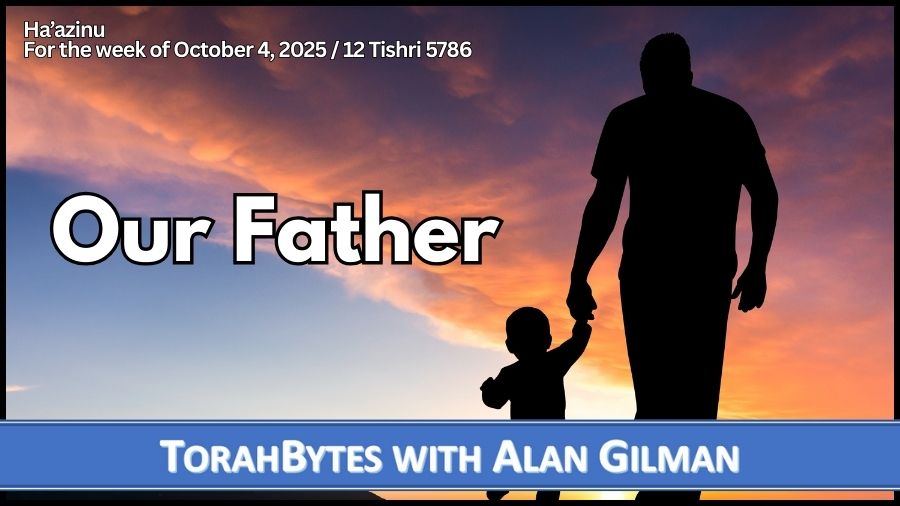

Do you thus repay the LORD, you foolish and senseless people? Is not he your father, who created you, who made you and established you? (D’varim/Deuteronomy 32:6)

It is fairly common among scholars to downplay the presence of key New Testament concepts found in the Hebrew Scriptures. These include, for example, forgiveness, life after death, and the complex unity of God. While it is correct to note that there is a difference regarding the prevalence of such concepts within these two sections of the Bible, it is incorrect that a relatively low amount of occurrences necessarily implies a lack of importance.

One such concept is the idea of “God as father.” In the New Covenant Writings (the New Testament) it is the chief identifier of God. Yeshua almost exclusively spoke of God in this way. He also instructed his followers to address God as “Our Father.” One might regard this shift in emphasis as an intentional contrast to earlier scripture in the sense that under the Old Covenant, God was seen as distant and detached, while Yeshua introduced a more intimate and familiar version of God. Both Christian and Jewish thought often want to find contrasts like this in order to disassociate Christianity from Judaism. But to do so, one needs to ignore what is really going on in the Bible.

It is true that God as father is a rarity in the Hebrew Scriptures, but it is there a few times, including its first occurrence found in this week’s parsha (weekly Torah reading). And that’s in addition to other references to God having father-like characteristics.

Moses’ use of “father” for God as part of his final words to Israel is most instructive. After all that he and the people had been through the past forty years, and as he confronts the people regarding their inevitable unfaithfulness, he urges them to respond appropriately to God based on his being their father. Directly calling God “father” sheds light on what God said to Moses forty years earlier regarding his confrontation of Pharaoh: “Then you shall say to Pharaoh, ‘Thus says the LORD, Israel is my firstborn son, and I say to you, “Let my son go that he may serve me.” If you refuse to let him go, behold, I will kill your firstborn son’” (Shemot/Exodus 4:22-23). To mess with God’s people was to mess with his family. In the days and years ahead for Israel, does it matter how often the term “father” is used in Hebrew scripture? Isn’t one reference enough to be struck by the overwhelming nature of such a relationship?

The people of Israel were delivered from tyranny to serve a new master and Lord. Yet, this master was no tyrant. Instead, God, as father, was dedicated to care, provide, and guide his children. Tragically, it would remain difficult for Israel to accept God’s fatherly heart towards them. Due to the broken nature of humanity, the hearts of the people were constantly pulled away from God and his ways. Yet, our Heavenly Father would not give up. Instead, he determined to transform our nature into one in keeping with his own (see Jeremiah 31 and Ezekiel 36).

God’s role as father of Israel reveals to us God’s heart for all people. As our Creator, whose familial relationship with humanity was broken due to our first parents’ misguided and selfish actions, he longs for restoration. His heart is to regain a relational intimacy between a loving father and his wayward children. Made in his image, we all bear his resemblance, while our actions reflect the nature of rebels. God’s broken fatherly heart, however, could not accept our alienation from his love. And so, in the name of family, his Son, Yeshua the Messiah, completely gave himself up to restore God’s children to him. God’s determination as Israel’s father is that which cleared the way for people of all nations to have the opportunity to be equally part of his family.

We need to come to grips with the implications of God’s identity as our father. Sadly, this is obscured by the confusion over the general fatherly role in our society today. Too many people have suffered from absent or abusive fathers. It is said that we often envision God as a reflection of our earthly dads. But it doesn’t have to work that way. Whatever our experience has been with our natural fathers, we can look to the loving, powerful, close, communicative care of our Heavenly Father as revealed in Scripture. For he is our true father.

Scriptures taken from the English Standard Version