For the week of February 20, 2021 / 8 Adar 5781

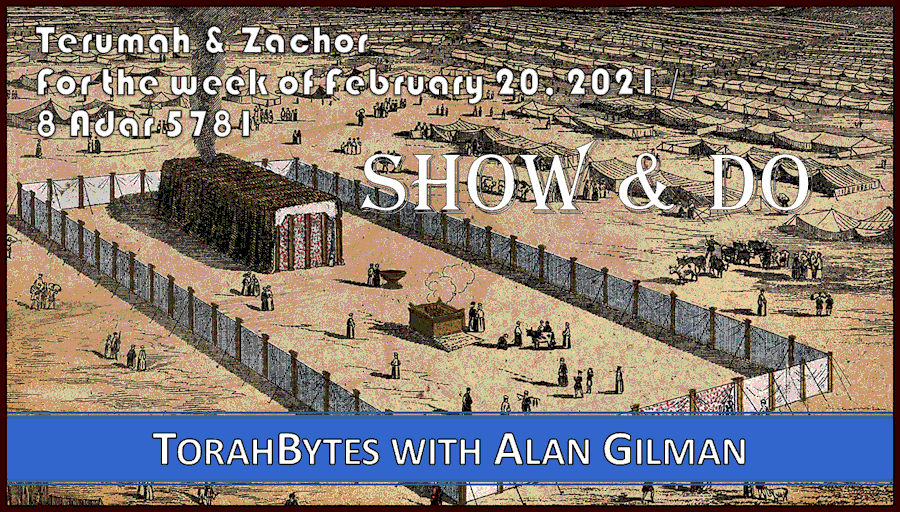

Illustration: The tabernacle erected in the wilderness, surrounded by an enclosure and miles of tents. Colored etching after W. Dickes. Courtesy of Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

Terumah & Zachor

Torah: Shemot/Exodus 25:1 – 27:19 & D’varim/Deuteronomy 25:17-19

Haftarah: 1 Samuel 15:2-34

Download Audio [Right click link to download]

Exactly as I show you concerning the pattern of the tabernacle, and of all its furniture, so you shall make it. (Shemot/Exodus 25:9)

There are two major sections in the second book of the Torah that are concerned about the building of the mishkan, usually translated into English as “tabernacle.” It was a large, yet mobile, complex designed as the locale for the offering of sacrifices and other priestly functions on behalf of the nation of Israel. Mishkan means, “dwelling place,” as it was to represent God’s dwelling among his people. This week’s parsha (English: Torah reading portion) through chapter thirty contains the instructions of the mishkan, its furnishings, and other related items, including the priests’ clothing and recipes for the special oil and incense. Then the actual construction is described beginning in chapter thirty-five through the end of the book, chapter forty.

Various people have attempted to draw or build accurate images or models – including life-sized versions – of the mishkan, but there is no way to ensure accuracy due to a missing ingredient in the instructions recorded by Moses. It appears that he was privy to something besides the details we read in the Torah. Not only did God tell him what to do, he also showed it to him. Because Moses saw what to do, he could also instruct the people on how to do it.

Before I continue, a word about the so-called Oral Torah. Jewish tradition claims that when God gave Moses his word to write down, he also told him other things that he did not write down, but instead was to be passed on orally. One of the main purposes of the Oral Torah is to interpret the written Torah. The Mishnah, which is the core of the Talmud is the written version of the Oral Torah. A scriptural basis for the Mishnah is the verse we are looking at, since it suggests that Moses was made aware of certain aspects of God’s revelation to Israel that he didn’t write down. However, this is no way legitimizes an oral tradition that most certainly was developed over time. Just because Moses was equipped with more than the written instructions for the Mishkan here doesn’t prove anything about other later rabbinic teachings.

What, then, might we learn from Moses’ experience of the mishkan? The people of Israel needed more than just “the what” of building it. They also needed “the how.” Throughout the ages people have abused the Bible because they thought that a simple reading was sufficient to live out its teachings. Armed with only the what, well-meaning, but otherwise naïve people have caused more damage than good. They claim to be taking God at his word but possess neither the sensitivity necessary to understand it nor his wisdom to live it out effectively.

When we read the Bible, we are not on our own. It’s a very old book, but its ultimate author is still alive. Not only that, he has made himself available to anyone who seeks him. In order to truly understand his word, we need to rely on him to show us how. This is not to say that our intuition or spiritual senses are reliable guides in themselves to understand the difficult and not-so difficult parts of scripture. The scriptures themselves provide interpretive boundaries for us. If Moses, having recorded the mishkan instructions, claimed that God showed that they were to build a boat, then everyone would know something was not right. I know that’s an extreme example, but it makes the point clear. If an interpretation of scripture is not well-supported by scripture, we should not trust it.

The same goes for any attempt to follow God’s instructions. Through the Ruach HaKodesh (English: the Holy Spirit) God speaks to his people in various ways. But too often we fail to wait upon him for how to do what he is calling us to do. Instead, we need to wait on him to show us, and then do.

Scriptures taken from the English Standard Version

Another outstanding teaching.

Thank you Alan.

“When studying the Talmud, how do you reconcile its perspectives with your faith in Jesus as the Messiah, especially given some of its challenging passages? For example, certain sections, like those in Sanhedrin 43a or Gittin 57a, have been interpreted by some scholars as containing derogatory references to Jesus, such as claims about his execution or afterlife punishment. How do you process these passages as someone who holds Jesus as the divine Son of God? Do you view these texts as historical artifacts, theological challenges, or something else? And how do you decide which parts of the Talmud to embrace or reject while maintaining your Christian faith?

On Specific Insults: In Sanhedrin 43a, there’s a passage that some interpret as describing Jesus’ execution and associating him with sorcery or leading Israel astray. As a Christian who believes in Jesus’ divinity and resurrection, how do you approach such a text? Does it undermine the Talmud’s value for you, or do you find a way to contextualize it that aligns with your faith?

On Theological Conflict: The Talmud, in places like Gittin 56b-57a, includes narratives that some claim depict Jesus in a negative light, such as suffering in the afterlife. For a Christian who affirms Jesus’ victory over death and his role as Savior, how do you justify engaging with a text that seems to contradict core Christian doctrines? Wouldn’t a true Christian find such passages incompatible with their faith?

On Authority of Scripture: As a Christian, you likely hold the New Testament as authoritative. Given that the Talmud, a product of Rabbinic Judaism, sometimes presents views that clash with the New Testament—such as denying Jesus’ messianic role or divinity—how do you determine which parts of the Talmud are worth studying? Are there specific teachings or passages you’d reject outright as incompatible with your belief in Christ?

On Cultural vs. Spiritual Value: Some Messianic Christians study the Talmud to connect with Jewish heritage, but passages like those in Shabbat 104b, which some critics argue mock Jesus’ birth or legitimacy, could be seen as deeply offensive to Christian beliefs. Do you read the Talmud purely for cultural or historical insight, or do you find spiritual value in it despite these conflicts? If so, how do you navigate the tension?

On Discernment and Faith: If you believe the Talmud contains material that insults or misrepresents Jesus, such as claims about his character or fate, how do you avoid compromising your faith by engaging with it? For instance, would you continue to study a text that you knew contained deliberate falsehoods about Christ, or would that lead you to set it aside as a Christian?

Why should anyone care about the Talmud who is a Christian?

I am not sure where you are coming from. I am a proponent of the inspiration and authority of Scripture, Hebrew Bible and New Covenant Writings. Any other literature should be critiqued on its own merit. As a Jewish person, I wish I was expert in Talmud, as it is so much a part of my people’s history and thought, but I only have one life to live. I would assume that many people reading these comments don’t understand the dynamics of Talmud, especially how it is full of discussion and a wide variety of opinions. As for the very few possible references to Yeshua of Nazareth, I don’t have an issue of encountering highly critical and dismissive viewpoints. That’s just par for the course in the world, not just the Jewish world. That said, I don’t regard the issues you mention as a cause for concern.

Thanks for sharing. It’s great to see your commitment to the authority of both old and new testament writings, and clear faith in Yeshua at the core of your beliefs. I can appreciate one’s desire to connect with their Jewish heritage by exploring the Talmud, even if it’s ones area of expertise. It’s understandable that you see its diverse opinions as part of its historical context, and your confidence in dismissing critical viewpoints about Jesus shows a strong foundation in your faith. That said, the Talmud’s occasional sharp-edged remarks, like those in Sanhedrin 43a or Gittin 57a, can feel like a bit of a minefield for Christians, given how they seem to clash with the truth of the New Testament. I’m curious—do you find any particular teachings in the Talmud especially meaningful for your walk with Yeshua, or is it more about understanding the broader Jewish conversation, despite its rough spots?

My understanding of the Talmudic sections in question is that it isn’t clear that the one being mentioned is Yeshua of Nazareth the Messiah or some other Yeshu or Yeshua, since that that was very common in its day. Even if it is in one of both, it doesn’t concern me, since I accept the New Covenant Writings as trustworthy. That there may be critiques or misrepresentations of him should be expected.